Disease Dynamics

I have a wide range of scientific interests, and enjoy collaborating with my Drake labmates. This has led to many projects that involve some combination of disease dynamics, machine learning, and modeling. Here are a few highlights.

Yellow fever in Brazil

Explore the project’s workflow on github.

The spread of yellow fever into areas previously thought of as low risk presented an ecologically interesting question- what’s changed about the disease dynamics in the region, and an important question for human health- can we predict areas of high risk for the disease. Michelle Evans and I started chatting about this problem, and decided this project required the combination of our unique skill sets.

Human infections of yellow fever in Brazil are the outcome of a series of events since it is a vector borne disease. We assumed that each human infection is the culmination of:

- a yellow fever outbreak in non-human primates

- a mosquito feeding on an infected non-human primate

- the mosquito becoming infectious

- the infectious mosquito feeding on a person susceptible to infection

- the person becoming infected

While mechanistic models have been developed to capture these events, we decided a statistical, machine learning approach would maximize the model’s predictive accuracy given the available data, intended timeline and our strengths.

We modified a machine learning method, bagged logistic regression, previously developed in the Drake lab based on our knowledge, and in some cases intuition of the disease system (see Schmidt et al.,2017 for the original bagged logistic regression method). Data limited us from answering our initial question about the 2017 outbreak, but we did find some interesting things.

First we noticed that the histogram of non-human primate species richness had a natural break which corresponded to a geographic break. Since non-human primates are such an integral component of the spillover process, we decided to build models for both regions (high and low non-haman primate richness) along with a national model.

From these models we were able to make the following conclusions:

- Non-human primate richness was an important driver regardless of model.

- Mosquito vector presence was not an important driver in the Amazon region, and a weak driver in the other models.

- Months that have abnormal temperatures or land use change rates are important for explaining spillover risk in the Amazon

- The regional model predicted strong seasonality in spillover risk in the Amazon, while the national model predicted a consistently high spillover risk.

These finding are important because they can be used to shape the timing, type, and location of interventions used to prevent future spillover of yellow fever in Brazil.

Read the full article at: Kaul, R.B., M.V. Evans, C.C. Murdock & J.M. Drake. 2018. Spatio-temporal spillover risk of yellow fever in Brazil. Parasites and Vectors 11:448. pdf]

Ebola in west Africa

Explore the project’s [workflow on dryad].

In December 2013, an 18-month-old boy contracted a fatal case of Ebola in a small Guinean village. The virus had spread to Guinea’s capital, Conakry, by March 2014. This was the first time human-to-human transmission took place in densely populated urban centers, and health officials struggled to contain the outbreak. By July 2014, the epidemic had spread to the neighboring countries of Liberia and Sierra Leone.

The summer of 2014 was filled with uncertainty. Health officials were struggling to decide where, and when to allocate resources. Clinical labs were overwhelmed, slowing the reporting of confirmed cases. Multiple NGOs and international aid agencies were working in similar areas with limited transparency.

The Drake lab joined the effort to provide more information to decision makers by modeling the outbreak. This task was challenging given the unknowns of a rapidly changing situation. We implemented AGILE project management relying heavily on daily scrums. Our early discussions focused on finding data streams to complement the case count data being aggregated. At the time, newspapers were reporting on community gatherings that led to new cases. From this, we were able to construct partial transmission trees and estimate the offspring distribution.

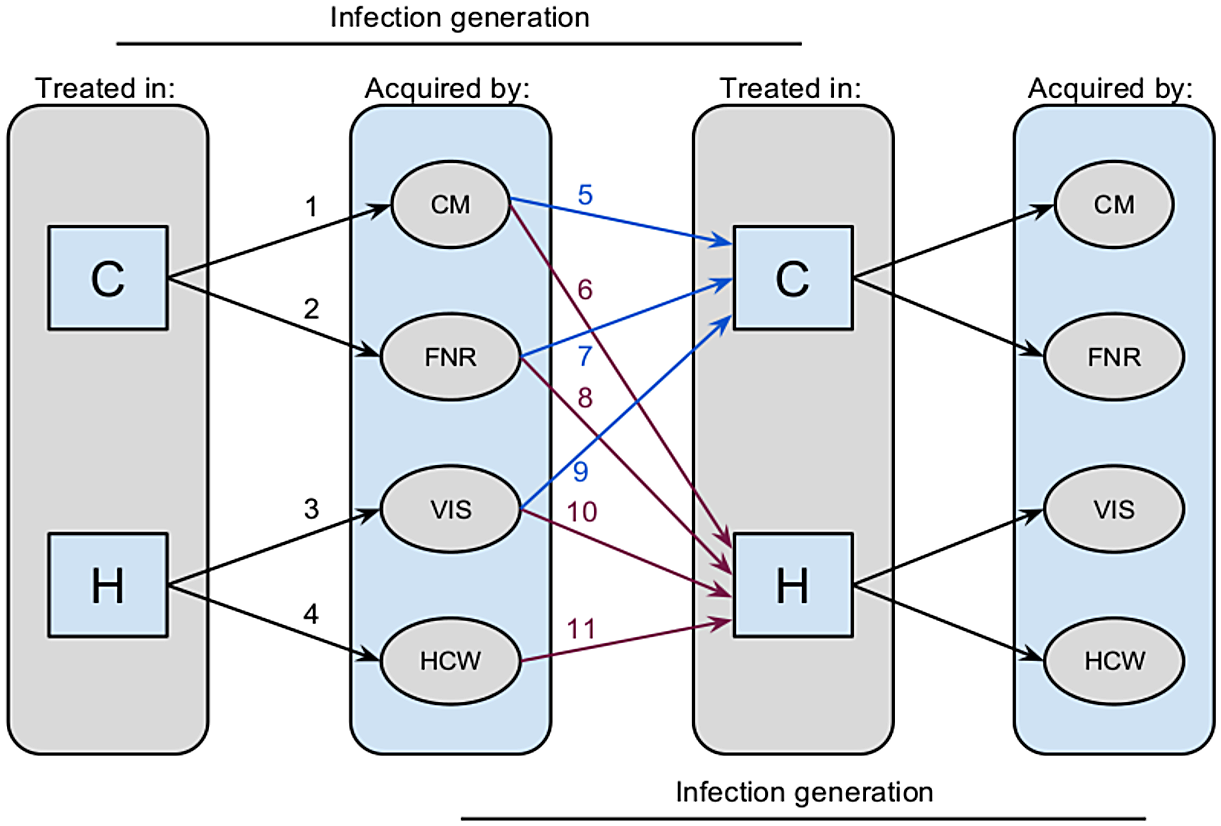

Using the offspring distributions, we developed a branching process model to determine the relative importance of nosocomial vs. community transmission, and hospitalization rates. We then used this model to assess different intervention and transmission scenarios.

Our results suggested the outcome of the epidemic depended both on hospital capacity and individual behavior.

Read the full article at: Drake, J.M., R.B. Kaul, L.W. Alexander, S.M. O’Regan, A.M. Kramer, J.T. Pulliam, M.J. Ferrari, & A.W. Park. 2015. Ebola cases and health system demand in Liberia. PLoS Biology 13:e1002056. [online]

White nose syndrome in the US

Story coming soon.

Read the full article at: O’Regan, S.M., K. Magori, J.T. Pulliam, M.A. Zokan, R.B. Kaul, H.D. Barton, & J.M. Drake. 2015. Multi-scale model of epidemic fadeout: Will local extirpation events inhibit the spread of White-nose Syndrome? Ecological Applications 25:621-633. [online]

Current disease dynamic projects

My current work has focused on understanding and predicting the spillover process in a changing world.

Members from the Center for the Ecology of Infectious Diseases (CEID) at UGA, including myself, formed a team to participate in the CDC Aedes challenge 2019. We have been developing monthly predictions of mosquito distributions using a suite of species distribution and time series models. This has been a great exercise in applying my quantitative ecologist skills to real world problems with less than ideal data sets. Github repository to be made public after challenge is completed in early 2020.

As a member of the CEID Spillover Working Group, I’ve been creating compartmental models of landuse change to predict changes in disease spillover risk with development. This work has led to the submission of a grant to the Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases divsion of the National Science Foundation, and a publication currently under review.